http://www.wired.com/dangerroom/2011/08/libyan-rebels-killed-top-merc/all/1

On a dark night in May, five employees of a prominent French private security company left a restaurant in the Libyan revolutionary capitol of Benghazi. Before they could return to their hotel, they were accosted by a group of armed rebels. As their colleagues explain it, they had little reason to believe there would be trouble: In the morning, the guards had an appointment with representatives of the rebel government to discuss a contract about securing a crucial material transit route from Cairo.

Very little about what happened next is clear. But one stark, bloody fact remains. Moments later, the rebels shot dead Pierre Marziali, a French ex-paratrooper who founded the security company, Secopex.

But this was no random hit by unruly gunmen who happened to wave the banner of opposition to Moammar Gadhafi. The Libyan opposition government quickly took Marziali’s men into custody, even though they were citizens of France, one of “Free Benghazi’s” most important foreign benefactors.

An official statement issued on May 11 accused the security contractors of “illicit activities that jeopardized the security of free Libya.” A promised investigation would determine if they were “spies hired by the Gadhafi regime.”

The curious incident made headlines — briefly. Then it faded away, a murky incident in a confusing war. Secopex has said next to nothing about the incident publicly — until now. Karen Wallier, a Secopex representative, told Danger Room that she herself “do[es] not have all of the answers” to what happened that night. But she said that the Secopex team “made no resistance” to the gunmen before Marziali was shot.

“The circumstances of his death were accidental,” Wallier added. “Allegations of espionage are totally unfounded.”

It is unclear if the Libyan government still believes Secopex spied for Gadhafi. But some in the private security business remain suspicious.

The Libyan rebel leadership has taken many steps in recent weeks to dispel the western suspicion, widespread when the uprising began in February, that the rebels are a shadowy band of unsavory characters. Since capturing most of Tripoli on Sunday, they’ve sounded notes about amnesty for former Gadhafi loyalists and pledged to retain most government bureaucrats.

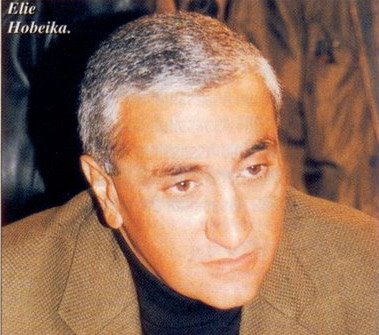

But the May killing of the security guards is a big reminder that there is much the west does not know about the post-Gadhafi Libyan leadership — and the bands of private mercenaries that made their way to Libya to cash in on the revolution. Was Marziali, pictured above, and his Secopex guards casualties of the fog of war? Did Secopex in fact have any connection to the Gadhafi regime?

Paris might have been expected to fight for the Secopex employees. It might have been expected to condemn Marziali’s killing. Instead, French Foreign Minister Alain Juppe, a key supporter of the rebels, declaimed any official links with Secopex.

“Those companies are private, as you’ve said: in other words, they have no relations with the public or in particular the French government,” he told a reporter on June 1, weeks after the killing. For good measure, Juppe referred to “reprehensible” activities taken “all over the place” by private security contractors.

By then, Marziali’s four employees had been freed and unceremoniously sent back to France. What they spent their time in Libya doing remains a mystery.

Secopex may not be familiar in the United States, but it’s one of France’s leading private military companies, one that industry observers compare to U.S. security giant DynCorp. Founded in 2003 by Marziali, a charismatic ex-paratrooper, the company got a brief burst of Anglophone attention in 2008, when it sought to station armed guards aboard commercial ships to protect them from Somali pirates — an idea that proved farsighted. Marziali even boasted of having a contract with Somalia’s interim government to build it an anti-pirate coast guard.

Secopex hasn’t said much about the killing or the detention. Its website announces that the company hasshut down operations until September. But its representative, Wallier, agreed to answer Danger Room’s questions — or some of them, at least.

According to Wallier, the Secopex team had been in Benghazi “for several weeks making contacts.” (That account was confirmed by another industry source who requested anonymity.) It scrounged a meeting with the Transitional National Council to pitch its services protecting the Cairo-Benghazi route. The meeting, scheduled for May 12, was important enough for Marziali to personally oversee it. He arrived in Benghazi on May 11 — the same day he died.

But Wallier did not address one of the biggest points of dispute with the Libyan government: whether Secopex met with any members of Gadhafi’s government.

According to the industry source — whose business interests are not in conflict with Secopex’s — the rebels who stopped the Secopex team discovered their passports had Tripoli entry stamps.

“When asked to explain how they got to Tripoli and what they did, they said they had been on a [security] detail for communications businessmen, but yes, they were in contact with Gadhafi intelligence and that they were asked to establish communications to supporters in Benghazi,” the source told Danger Room. “They claimed they refused the offer but could not explain how they got through the battle lines…. I think they were dirty. Their story didn’t hold water at all.”

Wallier did not respond to Danger Room’s questions about alleged Secopex interaction with Gadhafi intelligence; rumored interaction on behalf of “communications businessmen”; or possible entry into Tripoli. Nor did she respond to a request to interview the surviving Secopex guards.

Shortly after the deadly incident, the Transitional National Council pledged to conduct an inquiry into those allegations. But it is unclear if any such inquiry exists. Several efforts at contacting representatives for the interim Libyan government proved unsuccessful.

One thing is not in dispute: Ten days after the Secopex guards were taken into custody, the Libyans released them without charge, sending them back to France. Outside of Secopex, the incident has been all but forgotten.

Forgotten, perhaps, but not resolved. It could be argued that after the initial shooting, the Libyan rebel government acted responsibly by releasing the Secopex guards without charge, instead of keeping them detained. But if their release is an implicit admission of error, the Transitional National Council has never owned up to it — nor apologized to Secopex, France and Marziali’s family. Will that be the style in which it governs Libya?

By the same token, Secopex hasn’t fully explained what it was doing in Libya, a country that has become awash in private security firms and mercenaries. And with Gadhafi still on the loose and NATO sending mixed signals on putting peacekeepers into a wealthy country, it’s unlikely that private security firms are done with Libya.

But for now, Secopex is. “Mr. Marziali was a man of honor, having served his country for 25 years. He would not have worked against French interests,” Wallier said. “Under the circumstances, Secopex will not be returning to Libya.”.....